selected item

Pioneers of innovation: The battery that changed the world

This article was originally published in 2016. M. Stanley Whittingham was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry on October 9, 2019, and the following has been updated to reflect this news.

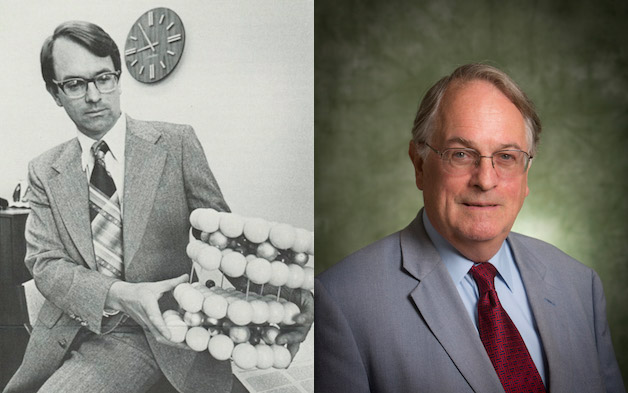

For this groundbreaking work, Dr. Whittingham was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Dr. John Goodenough of the University of Texas at Austin and Dr. Akira Yoshino of Meijo University in Nagoya, Japan. Today, Whittingham is a Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Materials Science at Binghamton University in New York.

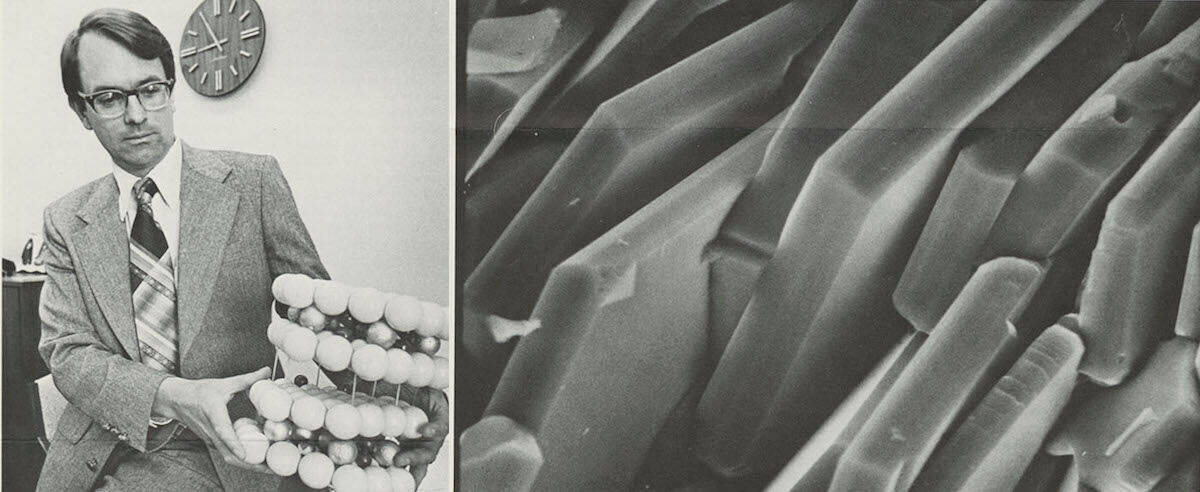

Prior to joining Binghamton, Dr. Whittingham worked at ExxonMobil, where his research paved the way for the development of the rechargeable lithium-ion battery. Specifically, he and his team discovered that when lithium ions were held between plates of titanium sulfide, the ions could move back and forth between the positive and negative contacts, creating electricity.

With lithium-ion batteries, “we have gained access to a technical revolution,” said Sara Snogerup Linse, a professor of physical chemistry at Lund University in Sweden who chairs the Nobel committee for the chemistry prize.

Evolving the battery design

Rechargeable batteries had been around for decades when Whittingham first proposed his version. But the rechargeable batteries at that time were bulky lead-acid cells – the kind still found in many cars today. And although the disposable carbon zinc batteries that power your remote control were prevalent, replacing them after each charge of a more energy-hungry device like a computer would be both annoying and expensive.

That’s what put Whittingham at the forefront of battery innovation.

Early research had suggested that the highly reactive metal lithium could be used to store energy, but Dr. Whittingham was the first to figure out how to make it happen at room temperature without the risk of explosion. His original design used titanium sulfide, a 2.5-volt material, and the intercalation design (or insertion of ions in a removable way) was sound and provided the basis for modern lithium-ion batteries.

In 1980, Dr. Whittingham worked with fellow Nobel laureate Dr. Goodenough at the University of Texas in Austin to improve his initial breakthrough by using metal oxides and higher, 4-volt materials. Building on that work on the other side of the world in Japan, Dr. Yoshino was able to develop the first commercial lithium-ion battery.

Powering technology for batteries

The high-energy-density lithium-ion technology now powers laptops, tablets, cellphones and most electric cars. It even allows solar-powered aircraft like the record-setting Solar Impulse 2 to continue flying after the sun has set. Power grids that are based on inconsistent power sources like wind or solar power are also beginning to rely on massive lithium-ion batteries to store energy for times when demand exceeds output.

Dr. Whittingham, Dr. Goodenough and Dr. Yoshino built on each other’s work and turned breakthrough research into an innovation that’s transformed how the world uses and stores energy.

Image credit: ExxonMobil Historical Collection, [identifier number: di_10643-di_10650], The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Explore more

Developing lower-emission solutions through research and development

3 min read

•

Engineering solutions to the plastic waste challenge

Solving the dual challenge: It takes patience and passion

The new generation of innovators creating next-generation energy

Applying digital technologies to drive energy innovation